Like a salmon returning to its birthplace, ocean plastic is finding its way back to its makers.

In the Pacific Northwest – a region of North America renowned for its seafood – researchers have found particles from our waste and pollution swimming in the edible tissue of just about every fish and shellfish they collected.

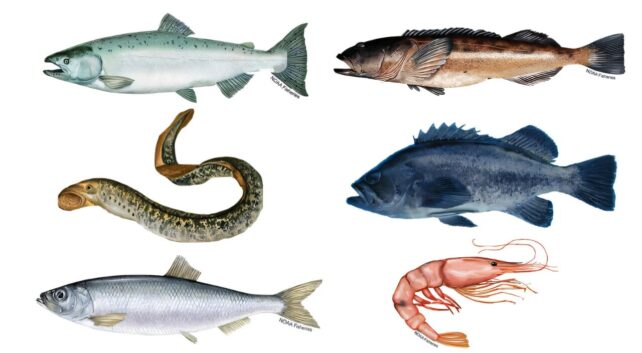

Of the 182 individuals caught on the Oregon coast or sold in the state’s markets, only two fish, a lingcod and a herring, had zero suspicious particles in their sampled slice of edible tissue.

The rest of the lot, including rockfish, lingcod, Chinook salmon, Pacific herring, Pacific lamprey, and pink shrimp, all contained ‘anthropogenic particles’, which included what are thought to be fibers of dyed cottons, cellulose from paper and cardboard, and microscopic pieces of plastic.

“It’s very concerning that microfibers appear to move from the gut into other tissues such as muscle,” says ecotoxicologist Susanne Brander from Oregon State University.

“This has wide implications for other organisms, potentially including humans too.”

Scientists have recently noticed that humans who eat more seafood tend to host more microplastics in their own bodies, especially those who consume bivalves like oysters or mussels.

How long those plastics stick around in the body and what they are doing to human health is unknown and demands urgent research.

Brander and her colleagues are not arguing that people should stop eating seafood altogether, but it’s important that consumers and scientists understand the level of exposure.

At this point, human-generated particles of paint, soot, and microplastics are so ubiquitous as to be inescapable. These pollutants now exist in the air, water, and in many meals other than seafood.

“If we are disposing of and utilizing products that release microplastics, those microplastics make their way into the environment, and are taken up by things we eat,” says ecologist Elise Granek from Portland State University.

“What we put out into the environment ends up back on our plates.”

The analysis from Oregon is the first of its kind in the region, and it shows that microplastics are widespread in edible seafood samples.

While it is limited to the most important species for the local seafood industry, the findings join studies from other parts of the world that have started to find microplastics in numerous seafood samples.

In the coastal waters of Oregon, filter-feeding shrimp had some of the highest concentrations of plastic waste accumulating in their bodies. Researchers suspect this is because shrimp exist in the upper water column, near the surface, where floating plastic and zooplankton converge.

“We found that the smaller organisms that we sampled seem to be ingesting more anthropogenic, non-nutritious particles,” explains Granek.

“Shrimp and small fish, like herring, are eating smaller food items like zooplankton. Other studies have found high concentrations of plastics in the area in which zooplankton accumulate, and these anthropogenic particles may resemble zooplankton and thus be taken up by animals that feed on zooplankton.”

When comparing freshly caught shrimp to samples purchased at the store, researchers found the store-bought shrimp contained more fibers, fragments, and films of plastic, possibly because of plastic wrapping.

Chinook had the lowest levels of anthropogenic particles in edible tissue, followed by black rockfish and lingcod.

Some of the researchers involved in the analysis are now working on ways to stop plastic waste from draining to the sea, but in the paper, the team agrees that the only effective way to stop the flow is to ‘turn off the tap’ on plastic production.

The study was published in Frontiers in Toxicology.