Quantum mechanics has long classified particles into just two distinct types: fermions and bosons.

Now physicists from Rice University in the US have found a third type might be possible after all, at least mathematically speaking. Known as a paraparticles, their behavior could imply the existence of elementary particles nobody has ever considered.

“We determined that new types of particles we never knew of before are possible,” says Kaden Hazzard, who with co-author Zhiyuan Wang formulated a theory to demonstrate how objects that weren’t fermions or bosons could exist in physical reality without breaking any known laws.

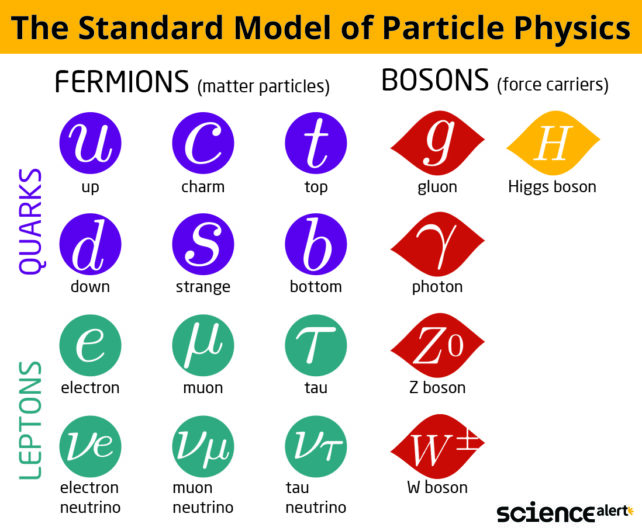

Fermions encompass fundamental particles that ‘build’ atoms, such as electrons and quarks. In more precise terms, they have a property that prevents them from occupying identical quantum states, effectively ensuring no two matching fermions can fill the same space.

“This behavior is responsible for the whole structure of the periodic table,” says Hazzard. “It’s also why you don’t just go through your chair when you sit down.”

Bosons are defined by a different measure to this property that allows them to pass right through one another like ghosts in a corridor.

Typically acting as force carriers like photons and gluons, bosons mediate interactions in ways that push and pull fermions into everything from protons to porcupines to potatoes to planets.

There is one notable exception to this strict rule of quantum-state segregation. Restricted to just two dimensions, some materials can give rise to a particle-like behavior that breaks the statistical laws expected of fermions and bosons, effectively allowing a unique swapping of quantum states.

Known as anyonsthese technical loopholes can’t extend into the three-dimensional space of our Universe and are therefore unlikely to be represented by any bona fide fundamental particles we’re yet to discover. Less a new aisle in the quantum hardware; they’re more like a novelty keychain you can pick up at the front counter.

Still, this has never stopped theoretical physicists from tinkering with the quantum descriptions of hypothetical particles to see what survives, operating in a field called parastatistics. Though an act of purely mathematical expression, doing so can reveal deeper truths about whether fermions and bosons are truly all there is, and if so, why so.

Since its inception in the early-to-mid 20th century, parastatistics has failed to find anything that can’t fall into the fermion or boson boxes. In fact, as quantum theories developed over time, it became increasingly clear that any theory developed through parastatistics would be indistinguishable from a universe with only fermions and bosons.

Wang and Hazzard think they have uncovered a reason to disagree. By introducing a second step of quantization distinct from previous methods, they’ve shown collective behaviors in materials can give rise to particles that act somewhat like anyons even as they turn corners in a three-dimensional universe more or less identical to our own.

The concept falls well short of mapping a path to a whole new class of particle, serving merely to show we might not want to close the book on the possibility yet.

“To realize paraparticles in experiments, we need more realistic theoretical proposals,” says Wang.

Yet knowing the Standard Model Hardware of quantum physics is yet to stock anything for general relativity, and has no room for bricks of dark matter or the equally mysterious springs of dark energy, having plans for expansion is worthwhile.

This research was published in Nature.