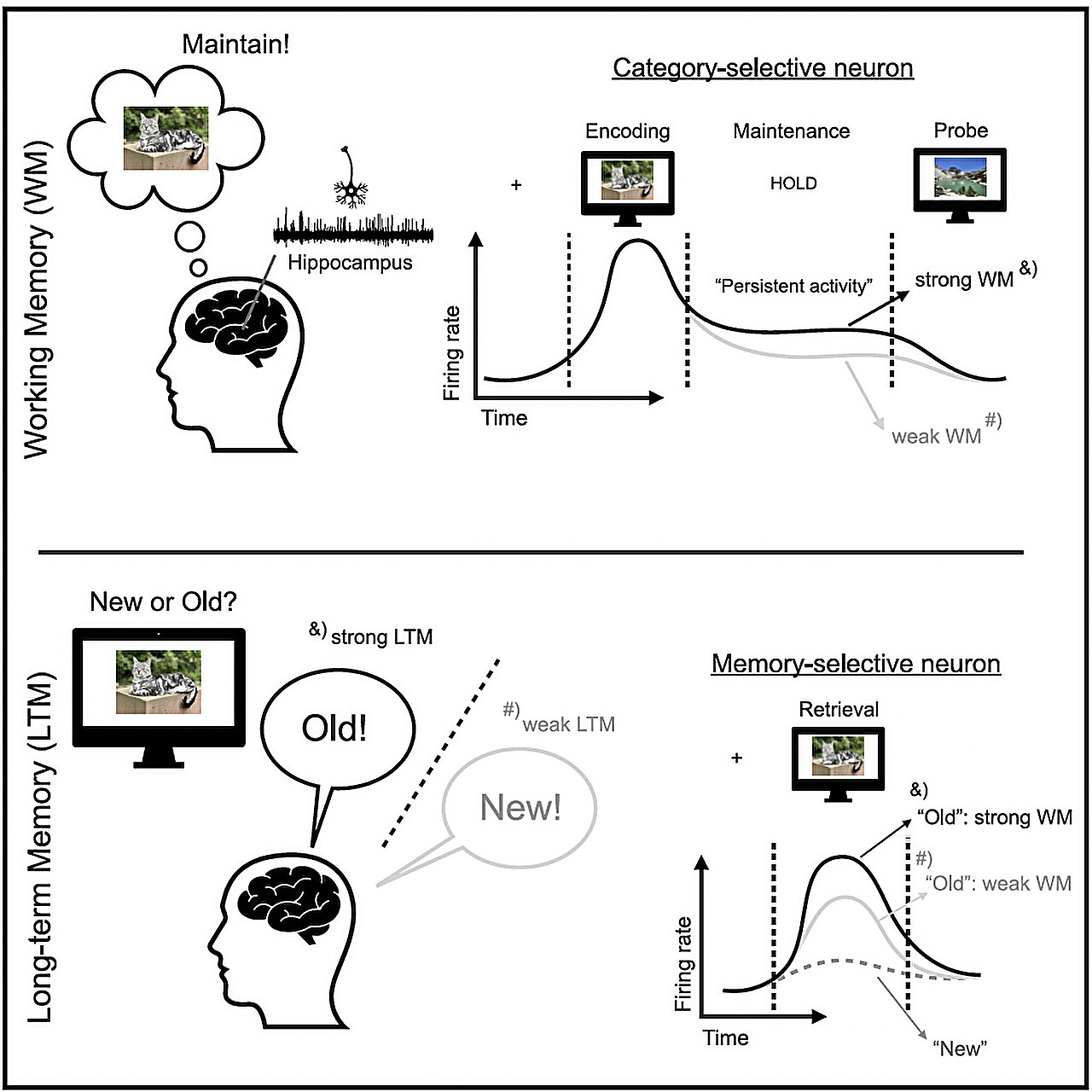

Credit: Daume et al. (Neuron, 2024).

The human working memory (WM) is the cognitive system responsible for the temporary storage and processing of information vital to task completion. In contrast, human long-term memory (LTM) is the system that holds information for prolonged periods of time, organizing acquired knowledge into distinct categories, such as facts, events, skills and habits.

For decades, most psychologists and neuroscientists have viewed these two memory components as separate systems, one tackling short-term and the other long-term tasks, supported by distinct neural processes. Therefore, most studies conducted so far have focused on only one of these systems, instead of exploring the potential connections between working memory and long-term memory processes.

Researchers at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and other institutes recently set out to simultaneously investigate the neural underpinnings of both WM and LTM, to determine whether these systems utilize some common mechanisms to store information. Their findings, published in neuronsuggest that the two systems interact in the hippocampus, with persistent WM activity predicting the formation of LTM.

“Working memory (WM) and long-term memory (LTM) are often viewed as separate cognitive systems,” wrote Daume, Kamiński and their colleagues in their paper. “Little is known about how these systems interact when forming memories. We recorded single neurons in the human medial temporal lobe while patients maintained novel items in WM and completed a subsequent recognition memory test for the same items.”

The researchers carried out experiments involving 41 patients diagnosed with epilepsy who had electrodes implanted in their brains via an invasive procedure to monitor their brain activity. These electrodes allowed the researchers to record the activity of single neurons in their medial temporal lobe, which includes several brain regions associated with memory encoding and information processing, particularly the hippocampus and amygdala.

Experimental design and behavioral analysis. Credit: neuron (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2024.09.013

The patients were asked first to complete a task designed to engage the WM and then a task that recruits the LTM. The researchers then compared the single-neuron recordings they collected while the participants were completing these two tasks, to determine whether the two systems shared any single-neuron mechanisms.

“In the hippocampus, but not in the amygdala, the level of WM content-selective persistent activity during WM maintenance was predictive of whether the item was later recognized with high confidence or forgotten,” wrote Daume, Kamiński and their colleagues.

“By contrast, visually evoked activity in the same cells was not predictive of LTM formation. During LTM retrieval, memory-selective neurons responded more strongly to familiar stimuli for which persistent activity was high while they were maintained in WM.”

Interestingly, the researchers found that persistent activity of category-selective neurons in the hippocampus while participants were storing information in their WM predicted the formation of LTMs. In addition, selective neurons associated with LTMs fired more when participants were presented with items that were associated with a strong WM activity.

“Our study suggests that hippocampal persistent activity of the same cells supports both WM maintenance and LTM encoding, thereby revealing a common single-neuron component of these two memory systems,” wrote Daume, Kamiński and their colleagues.

The results gathered by this team of researchers offer new insight into the neural underpinnings of WM and LTM processes, suggesting that they are linked by a common single-neuron mechanism. In the future, they could report additional studies focusing on this mechanism and exploring the link between the two memory systems.

More information:

Jonathan Daume et al, Persistent activity during working memory maintenance predicts long-term memory formation in the human hippocampus, neuron (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2024.09.013.

© 2025 Science X Network

Citation: Single-neuron mechanism may bridge gap between working memory and long-term memory (2025, January 10) retrieved 10 January 2025 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.